Jamaica’s reggae megastar received a hero’s welcome when he came home after seven years in a US jail. ‘No guts, no glory – that’s my genesis,’ he says in a rare interview

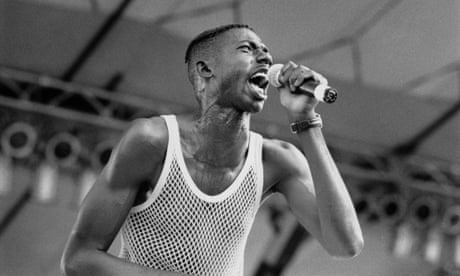

At the end of 2018, the reggae star Buju Banton returned to Jamaica after almost seven years in a US prison, and Norman Manley international airport was mobbed. His flight was delayed, the chants of “We want Buju” ramped up, then after a brief prayer huddle in the customs area, he pushed into the arrivals hall to pandemonium. It took a phalanx of hi-vis-wearing airport workers to hustle him through to the waiting police motorcade, a task not helped by the workers’ attempts to get selfies with their charge.

It was a hero’s welcome because, despite being convicted in the US of intention to distribute cocaine, Banton is a Jamaican hero. For his first post-prison concert, at Kingston’s National Stadium, about 30,000 people were packed in with many more enjoying it from outside.

The love Banton gets from the Jamaican people is the sort of deep cultural bond that goes way beyond his considerable achievements. Dennis Brown had this relationship, as do Yellowman and Usain Bolt, because they represent and celebrate the Jamaica that doesn’t make it on to tourist-board literature – as Banton himself drily puts it, “without any redaction or Photoshopping”.

“I don’t know how many people turned out that night,” he says. “The numbers don’t really matter – it’s the celebration that matters, the gathering of the people. I love my people, they know that, just as I know my people love me – they know a grave injustice took place. There was a magnetic energy generated by the people in the National Stadium that night. If you had a meter you could have measured it!”

After two trials – the jury was unable to reach a verdict in the first – Banton was found guilty of illegal possession of a firearm and conspiracy to possess 11lb of cocaine with intent to distribute. He was sentenced to 10 years, reduced by two when the gun charge was dropped. The case rested on recordings made by a Drug Enforcement Administration informant who received $50,000 for his services; one video played to the court appeared to show Banton sampling the drug. He denied any involvement in any drug deal itself, maintaining it was all talk, and the prosecution accepted he had no financial involvement. But conspiracy is talk – it only needs somebody to be talking to somebody else about something illegal.

Cover Art for new album

Cover Art for new albumIn the 18 months since his release, Banton has never talked about the conviction or his time in jail. When pushed, he calls it “an improvised hell” he got through by reading, meditating and reflecting on life – his own and in general. “Time and space is relative,” he says. “You have to shield your mind, and as a man of hope and a man of faith I can see the world is right there and I am right there, but can absent myself from the mundane existence.” He seems untouched by the experience, physically and mentally, the same amenable, generous and humorous person I have met on previous occasions.

He has long disavowed Boom Bye Bye, the murderously homophobic single he wrote and recorded as a 16-year-old and which was released without his knowledge when he hit big. To remind people, he issued a statement on his release from prison: “I recognise that the song has caused much pain … I am determined to put this song in the past and continue moving forward as an artist and as a man. I affirm once and for all that everyone has the right to live as they so choose.”

Banton shares a background of extreme hardship with so many Jamaicans – “standpipe poverty”, he calls it, as the houses in his part of Kingston had no running water – but his particular affinity with his homeland is due also to his Maroon ancestry. He can trace his roots back directly to the rebel coalition of runaway slaves and indigenous people who, in the 18th century, retreated to the mountainous interior and waged a 10-year campaign against the British. The Maroons’ guerrilla tactics were so successful that they were granted their own land and autonomy from colonial rule. Today the Maroons’ Accompong village remains apart from the government and plays a big part in the black Jamaican psyche: rebels who refused to bow down.

“My Maroon heritage is very important to I, because it kept I close to my roots and my origins,” Banton says. “I think about it every day. It kept me solid through the recent years, because I know how my people suffered long and they fought hard for freedom. It puts my struggles into perspective and shows why every black man have to fight.” In the grounds of his comfortable Kingston home, Banton has a circular Maroon hut. “The tabernacle! It’s built of thatch and wood and it’s a place of meditation and contemplation, a place appropriate to my roots and how I relate to the world.”

On a more prosaic level, Banton’s closeness to the Jamaican people comes from his sound system days in the late 80s, at a time when the island’s dancehalls were assuming fresh cultural currency as a generation of artists prioritised domestic over international audiences. From the age of 15, Banton apprenticed on the Rambo International sound system, which travelled all over the island.

Recording was an obvious next step. “I record my first song when I was 16 years old. [Dancehall star] Clement Irie had taken me up to the Blue Mountain studios in Kingston, I thought just so I could see what a recording studio look like. Straight away I became very nervous because I’m seeing all these people I only know from on record and they’re all wearing gold chains as big as a car rim – or bigger! Then they put me in the booth with headphones on, and told me when the red light comes on, that’s my cue. I started doing the number and I didn’t stop until the three minutes was up.” This became The Ruler. “I couldn’t really remember doing it, I just remember how they was all impressed because they’d never seen someone sing from top to bottom of a tune and not make a mistake.”

Within a couple of years, Banton was the island’s top recording artist; by 1992, he had beaten Bob Marley’s record for Jamaican No 1s, and Donovan Germain, the boss of Penthouse Records, gave Banton the run of the studio. There, together with the producers Dave and Tony Kelly, confidence met musical intelligence to create the Mr Mention album.

This was an experiment born out of “wanting to come to the dancehall with a complete body of work. We was young men fresh out of school and we had the studio at our disposal, our brains bubbling, bursting. We wanted to make music that would work in the dancehall. We had a genuine interest in going on a journey.”

Mr Mention became the bestselling album in Jamaican history. Its 1993 follow-up, Voice of Jamaica, made a broader statement still, shifting between love songs, dancehall bangers, hip-hop flavours (Busta Rhymes features) and social concerns. Then came ’Til Shiloh and Inna Heights, stunningly crafted albums of melodic Rasta reggae conceived during his conversion to Rastafari. “Those were tremendous bodies of work, messages I received when I was going through my awakening: Rastafari and reggae music are together.” The music aimed to “re-educate the masses” about the religion and culture: “We have shared our music with the world and we see many people wearing dreads, but they don’t understand the teachings.”

“You have to move forward – it’s liberation,” he says. “There is no future in the past. Let it serve as a guiding force, but that’s all. Music is in my blood. I can’t lock myself in a single room; evolution is what you’re supposed to do.”

At 46 and free from the hell of the last few years, Banton has earned his place as reggae’s elder statesman, and is a genuine inspiration for the broadminded generation of Jamaican artists coming through, the likes of Chronic Law, Jaz Elise and Leno Banton, son of star deejay Burro Banton, to whom Buju’s stage surname is a tribute. He is keeping reggae’s roots where the ground has always been most fertile: the regular Jamaican people. According to culture minister Babsy Grange, they “would have loved him just the same even if he’d come back in handcuffs”.

• Buju Banton’s new album, Upside Down 2020, is out now.

Comments