By: Tom Fordyce - BBC Sports

From a man who has delighted in pulling off the impossible, this was perhaps the greatest miracle of all.

We often compare Usain Bolt to Muhammad Ali - not for his political convictions but his charisma, for the effect he has had on his sport, for the impact he has made on the world outside it.

Coming into this World Championships 100m final on a dark, sweaty night in this giant ball of cold steel, it seemed that we might get the old showmanship but not the old magic.

The best we could hope for, with the twice-banned Justin Gatlin on a 28-race unbeaten run, with Bolt injured for much of the summer and stumbling in his semi-final, was a defeat to set up a future redemption.

BBC Sport commentator Steve Cram |

|---|

"Usain Bolt will walk away from the race so proud of himself, and that's from someone who has so much to be proud of during his career. This may well have been his finest day." |

Ali's defeat by Joe Frazier at the Garden in 1971, without which the Thrilla in Manila could never have happened; Bolt knocked out in the Bird's Nest to set up the Revival in Rio in 12 months' time.

Yet it seemed too great a burden for a man who has looked not only mortal this summer but for the first time truly fallible.

Bolt had raced the 100m on just two days this season before arriving at the scene of his unforgettable coronation in 2008. So bad was his pelvic injury that not until late July did he record a time that hinted he could even be competitive in Beijing.

Ali could compensate for his declining speed and the power and fury of his rivals with ringcraft and tactics, by scheming and slipping and refusing to surrender until the other man had fallen.

The 100m does not afford those nuances. Nine-point-something seconds. Which man gets there first. There is no hiding place and no time for comebacks.

And yet Bolt, once again, proved us all fools.

His was an ugly heat and a horrible semi-final. He almost fell from his blocks and had to fight with eyes-wide desperation to even make the final.

What could he possibly do up against the relentless consistency of Gatlin? These have been the American's times this year: 9.74secs, 9.75, 9.75, 9.78. In his heat he ran 9.83, in his semi 9.77.

When Ali went to Zaire to take on the dead-eyed might of George Foreman, witnesses to the build-up spoke of the fearsome percussive force of the ascendant's right hook on the heavy bag.

So it was with Gatlin's times. Bang. Bang. Bang.

Bolt in numbers |

|

|---|---|

6 - Bolt won his first Olympic gold medal at the Bird's Nest, in the 100m, and has since gone on to collect a further five. |

9.58 - The Jamaican holds the world record for the 100m (9.58) and the 200m (19.19). |

3 - Prior to Beijing, Bolt had only competed in three 100m races in 2015 because of injury. |

9.87 - Bolt's season's best in the 100m coming into the World Championships. |

I spoke to Gatlin's camp in the afternoon before this showdown, heavy grey skies and dark thunder clouds over the city, a portent for the superstitious of what might lie ahead for the sport if a man who has twice been banned for drug offences were to win its premier event.

There was not just confidence but near certainty. There was talk of a 9.6-something. There was talk of how much the 33-year-old American wanted the lane next to the ailing Jamaican, so he could shock Bolt mentally in the first few metres before destroying him physically in the next 95. There was talk of a new era.

Even on the blocks Bolt seemed beset by self-doubt. There were the usual games - pretending to smooth his hair back, playing peekaboo into the camera's lens when the world looked closer - but also sweat on his brow and a flicker to his eyes.

Lots of people have never seen Bolt beaten. He has been - by Yohan Blake at the Jamaican trials in 2012, by Gatlin himself in Rome two years ago - but never when it really matters, never on the world stage.

This seemed the moment for the old narrative to fall apart. Instead it was Gatlin - relentless Gatlin, predictably brilliant Gatlin - who cracked and fell.

From the blocks Bolt was ahead. At 20 metres he was relaxed. By 40 he was driving, and by 60 Gatlin was tying up - technique coming apart, rhythm going, those 28 victories falling away in his slipstream as the yellow blur to his left refused to come back to him.

Ali beat Foreman through rope-a-dope and bravery and immense mental fortitude. Bolt found his own way: belief when others wondered, speed when we feared it gone, a strength in body and mind that Gatlin could not match.

Bolt's reaction time to the gun was six thousandths of a second faster than Gatlin's. By the end the margin had stretched only a little, to a single one-hundredth of a second. A fraction between them, a chasm in charisma and class.

This was never good vs evil, as some tried to bill it in advance. Gatlin is a dope cheat, not a serial killer or child abuser.

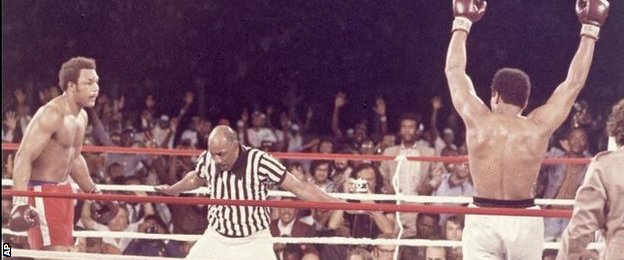

Muhammad Ali, arms raised in victory, beats George Foreman in the eighth round of their Rumble in the Jungle title bout in Kinshasa, Zaire (Now Congo Democratic Republic), in 1974

Neither is it a new plot line. There have always been dopers and deceit among the fastest men and women in the world, whether it is Ben Johnson in Seoul or Carl Lewis failing three tests before he even got to those 1988 Olympics, Marion Jones winning in Sydney 12 years later on a blend of EPO and human growth hormone or her one-time husband Tim Montgomery using the same to break the world record before ending his career in jail for dealing heroin on the streets.

Bolt said before Sunday that he couldn't save the sport on his own. He hasn't. There were three other one-time dopers in this final. Tyson Gay, Mike Rodgers and Asafa Powell send out a message of their own: cheat and you can still prosper, cut a deal and you can come back in the time it takes a torn hamstring to heal.

But on a night that could have ended with the sport no longer teetering on the abyss but plummeting over it, the victories of Bolt and, a few hours earlier, Jessica Ennis-Hill in the heptathlon, gave the believers something to cling to and the doubters reason to perhaps think again.

One day Bolt will be gone, and with him the greatest wonder of our sporting age. Athletics must learn to both flourish without him and win some of the battles he has fought almost singlehandedly over the past few years.

For now we should give thanks for him and Ennis-Hill: smiling assassins of cynicism, unstoppable reminders that sport can sometimes be about hard work and heroics as well as the darker, dispiriting side of human nature.

Comments